The Finnish welfare state succeeded well in softening the impact of the coronavirus crisis on low incomes and inequality

20.1.2021 Blog Tomi Kyyrä (VATT), Jukka Pirttilä (HY ja VATT) ja Terhi Ravaska (VATT)

Based on the up-to-date data of the Helsinki GSE Situation Room, we have been able to monitor the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic and restriction measures on various groups of employees and companies. But what kind of an impact has the coronavirus crisis had on disposable income, low incomes and economic inequality?

We examine this question by utilising both the Situation Room data and the SISU microsimulation model. Our work is closely related to the previous analysis of our colleagues in the Social Insurance Institution of Finland, Kela. Our focus is more on how well the automatic stabilisers of the public sector have functioned during the coronavirus pandemic. By automatic stabilisers we refer to the mechanisms which, as earned income decreases due to unemployment, for example, reduce the taxes and increase the benefits and income transfers to soften the blows on disposable income of households and, consequently, on total consumption and the level of economic activity.

First, based on the Situation Room data, we calculated the change in the risk of job loss (permanent or temporary lay-off) in the first half of last year for different employees. The employees were divided into groups based on age, gender, education, occupation and residential area. After that, the dataset that underpins the SISU model was modified so that some employees become unemployed based on their group-specific risk. The model is used for analysing how the financial status of households changes from the baseline scenario (from the model's 2018 base dataset) compared to the case that takes account of the increased unemployment due to the coronavirus pandemic and restriction measures.

While the average market income decline was around 4.5 per cent, the disposable income decreased by only about 1.8 per cent. In other words, the automatic stabilisers of the welfare state seem to be working quite well!

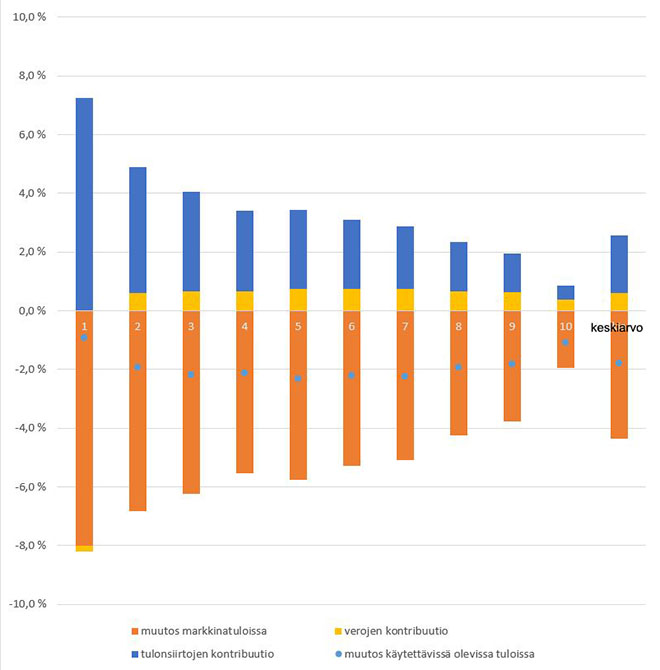

The impacts on the disposable income of all wage-earner households by income deciles compared to the time before the crisis are shown in the figure below. While the average market income decline was around 4.5 per cent, the disposable income decreased by only about 1.8 per cent. The impact was the highest in the middle of the income distribution and the lowest in the lowest income decile, where the replacement rate (i.e., the share of loss of earnings covered by benefits and income transfers) is the highest. Income transfers appear to play a strong insurance role at the low-income end, whereas at higher income levels the reduction in the tax burden has a more significant impact.

Figure 1. Changes in income, all employees.

If we examine only the households where at least one member has become unemployed, the fall in disposable income is clearly higher. On average, it is approximately 18 per cent, but the loss profile across income groups is similar to that of all households. The households with a young, male or low-skilled reference person suffer more than others.

According to our calculations, the low-income rate (at-risk-of-poverty-rate) rose from 13.05 per cent to 13.75 per cent (0.7 percentage points) and the Gini coefficient, measuring income inequality, rose from 0.277 to 0.28 (0.002 units). However, without the softening effect of automatic stabilisers, the increase in poverty rate would have been 2.3 percentage points and the increase in the Gini coefficient would have been 0.015 units. It can, therefore, be said that taxation and income transfers cut the increase in the risk of poverty by 69 per cent (1 - 0.007/0.023) and the increase in inequality by 84 per cent. In other words, the automatic stabilisers of the welfare state seem to be working quite well!

We have used many simplifications in our calculations. We have only examined the situation of wage-earner households and, for their part, only the situation in which a person becomes fully unemployed or laid-off for a full year. In the future, account should also be taken of the changes in the situation of entrepreneurs and the drop in income among those who have had to work part-time against their will. Furthermore, the modelling should be extended by taking into account the impact of additional measures taken during 2020 (such as easier access for entrepreneurs to unemployment benefits). We intend to carry out such further analysis in 2021. We will also report our research results in the international research project on inequality, The IFS Deaton Review: Inequalities in the 21st Century, led by Nobel Laureate in economics, Sir Angus Deaton from Princeton University. VATT will produce a chapter on the development of inequality in Finland for the publication.

Additional information:

Professor Jukka Pirttilä, VATT Institute for Economic Research and University of Helsinki, Tel. +358 295 519 426

Jukka Pirttilä

Terhi Ravaska

Tomi Kyyrä

Blog

Blogit

Blogit

Business regulation and international economics

Income distribution and inequality

Social security, taxation and inequality

coronavirus

income differences

income distribution

inequality

unemployment