Persistence of unemployment increases the costs of the economic crisis

29.4.2020 Blog Jouko Verho

The coronavirus pandemic has caused a global economic crisis. Now that the initial shock has passed, public debate has begun on the economic consequences of the crisis. It is clear that Finland is plunging into a recession, but it is yet to be determined how deep. Compared with the recession of the early 1990s, a common feature is the collapse of total demand, which seems to lead to a sharp rise in unemployment. Could the lessons of the 1990s recession be applied to solve the current crisis?

The employment of those laid off during the recession permanently decreased

In my recent study, I analysed the re-employment of those who were made redundant during the 1990s recession in the years following the recession1. I looked at workers whose plants were permanently closed in 1991-1993. I compared the displaced workers with a very carefully matched comparison group composed of workers who were not laid off during the reference year (but possibly in subsequent years). I followed the labour market outcomes of the worker cohorts formed up to the beginning of the next economic crisis, i.e. the financial crisis that began in 2007.

The challenge in examining the impact of unemployment is that layoffs do not target workers randomly. Companies in difficulty close down their least productive activities first. Thus, a direct comparison between those who have retained their jobs and those who have lost their jobs leads to selected study groups. Scientific literature, therefore, seeks to avoid the selection problem by analysing, for example, closures of entire plants or other mass layoffs. In economic crises, as a rule, layoffs target plants and workers in a more sporadic manner.

In my study, an interesting and somewhat dramatic feature of the research design was that more than 90% of the workforce in plants closed as a result of a bankruptcy or reorganisation of the company’s operations experienced unemployment after the closure for at least a period of time. In this respect, the study design differs from the extensive scientific literature analysing the impact of job loss on earnings2.

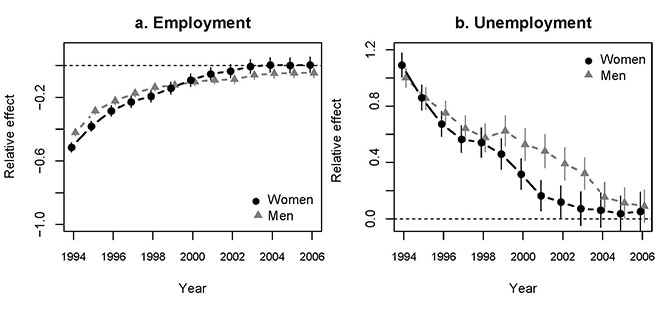

The study established that the earnings and employment of those made redundant during the early 1990s recession dropped to around 58% compared with the comparison group, and remained weak for years after the recession. The diagram below shows the dynamics of the effects of displacement in the years after the recession. The effect on employment slowly declines year on year, both for women and men. The negative effect on employment among women disappears approximately ten years after the recession, but the employment of men remains permanently a few per cent below the comparison group.

The right-hand panel examines the effect of displacement on unemployment. It largely develops as a mirror image of months in employment and is almost fifty per cent more common among the displaced workers five years after the recession. For women, the effect on unemployment persists a few years longer than the effect on employment. In the case of men, there is a sharp jump in the trend in 1999.

Overall, the re-employment of those laid off during the 1990s recession was slow and unemployment had a strong tendency to prolong. Due to the high number of displacements, this was reflected in the high unemployment rate at the macro level in Finland.

Figure: Effect of plant closure on employment and unemployment of displaced workers in 1994-2006. Months in employment and unemployment of those laid off in 1991-1993, relative to the matched comparison group composed of persons who maintained their jobs.

Steps should be taken to combat unemployment persistence

When determining economic policy measures, it is essential to understand to what extent unemployment tends to prolong during a recession. At the individual level, the key concept is ‘duration dependence’, i.e. to what extent unemployment persistence reduces employment opportunities. Two key mechanisms are at the root of this.

First, when an employee is displaced, the human capital generated by the employee in the company is lost, i.e. competence that cannot be used directly for the benefit of another employer. During normal cyclical fluctuations, this is an inevitable part of competition, but in a crisis situation, such losses can become unnecessarily high.

Second, it is more difficult to re-enter employment during a recession, and unemployment may be prolonged. In such a case, the human capital of the employee, i.e. their competence and factors affecting their ability to work, may start to erode. Furthermore, depreciation of human capital can cause permanent and long-term losses to the national economy, as appears to have occurred in Finland as a result of the 1990s recession.

To what extent can the lessons of the 1990s recession be applied to the current economic crisis? This is difficult to estimate until the depth and duration of the coming recession is known. The 1990s recession lasted several years, and its consequences were very different compared to the more short-term financial crises. In addition, the Finnish economy has undergone a major structural change in 30 years, and each economic crisis has its own specific characteristics. The corona crisis particularly affects the services sector, whereas in the 1990s recession, the end of Soviet trade particularly shocked Finland’s export sector3.

It is clear, however, that when determining business support and employment policy measures, attention must be paid to the persistence of unemployment and its prevention. Otherwise, the losses can become significant from the point of view of both individuals and the national economy.

References:

1) Verho, J. (2020). Economic Crises and Unemployment Persistence: Analysis of Job Losses During the Finnish Recession of the 1990s. Economica, 87(345), 190-216.

2) Couch and Placzek (2010) provide an overview of US studies on the effect of displacement on earnings. Earlier Finnish studies on the effects of displacements carried out during the 1990s recession have been carried out by Korkeamäki and Kyyrä (2014) and Huttunen and Kellokumpu (2016).

Couch, K. A., & Placzek, D. W. (2010). Earnings losses of displaced workers revisited. American Economic Review, 100(1), 572-89.

Huttunen & Kellokumpu (2016): The Effect of Job Displacement on Couples’ Fertility Decisions. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(2), 403-442.

Korkeamäki, O. & Kyyrä, T. (2014). A distributional analysis of earnings losses of displaced workers in an economic depression and recovery. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 76(4), 565-88.

3) Gorodnichenko et al. (2012) underline the importance of the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of bilateral trade in the 1990s recession, whereas Honkapohja and Koskela (1999) place greater emphasis on the importance of financial markets.

Gorodnichenko, Y., Mendoza, E. G. & Tesar, L. L. (2012). The Finnish great depression: from Russia with love. American Economic Review, 102(4), 1619-44.

Honkapohja, S. & Koskela, E. (1999). The economic crisis of the 1990s in Finland. Economic Policy, 14(29), 399-436.

Jouko Verho

Blog

Blogit

Blogit

Column

Income distribution and inequality

Labour markets

Labour markets and education

Social security

coronavirus

labour markets

unemployment

unemployment duration