EU is dreaming of a green future but has little to show by way of cleantech innovations – which path will Finland take?

2.6.2020 Blog Anni Huhtala

The European Commission presented the European Green Deal in December last year. The programme was also discussed in the Finnish Parliament just before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. As the EU is planning pandemic rescue packages, it is worth recalling the Sustainable Europe investment programme envisaged in support of the European Green Deal. Investments totalling at least EUR 1,000 billion were planned for the period 2021–2027 and half of this sum would have been financed from the EU budget.

It is interesting to see whether the crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic will prompt the EU to change the European Green Deal. At least the rhetoric about climate stimulus might be suitable for the aftercare of the illness.

The European Green Deal was supposed to be the new growth strategy transforming the EU into a ‘fair and prosperous society, with a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy’. Under the programme, the EU was expected to be carbon-neutral by the year 2050 and the tightening of the existing greenhouse gas emissions targets was set as an interim target.

According to the macroeconomic scenario models produced by the European Commission, carbon neutrality by the year 2050, the key objective of the green transformation, could be achieved with little negative impact on growth in the EU economic area. Greenhouse gas emissions would be reduced by about 80% and the remaining emissions reductions would be achieved through carbon capture and storage (CCS) and carbon sinks.

In the Commission’s scenario, green transformation and structural change in the EU economic area would be driven by a change in energy generation methods. There would be a significant reduction in the added value of energy production, traffic and transport based on fossil fuels. The carbon-neutrality target would be achieved through research and development and substantial investments in clean technology. The global competitiveness of the European manufacturing industries would also be largely based on the ability to develop and use clean technology.

Are the innovation hopes unfounded?

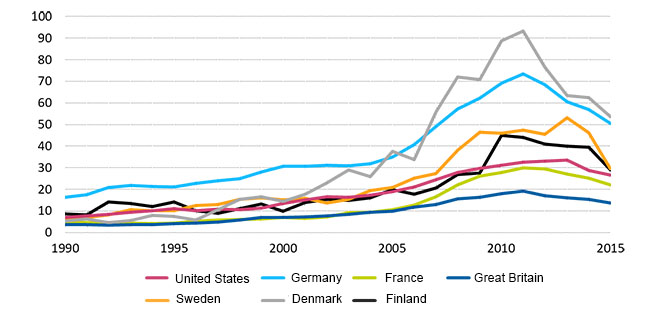

How do countries compare in the development of clean technology? The patents for climate change mitigation technology in the United States and a number of European countries are shown in Chart 1. The number of patents per one million inhabitants has been calculated using OECD patent statistics.

Chart 1. Patents for climate change mitigation technology (per one million inhabitants) Sources: OECD.Stat. and Huhtala (2019, 186)

The comparison shows that even though Finland has been doing reasonably well in international patents rankings, we are not at the top of the list. The success of Denmark is largely explained by wind power patents. The breakthrough and improved profitability of the wind power technology are based on investments in long-term research and development, which began in Denmark earlier than in such countries as Finland.

It is interesting to note that the number of patents for clean technology had declined by 2015 (the latest year for which statistics are available). After a period of strong growth, the number of patents peaked around 2010. This has also been the global trend. Popp et al. (2020) have also highlighted this and in their recent publication, they present hypotheses explaining why this has also happened in the energy sector, which is expected to undergo a major transformation.

Why are so few patents and new technology companies created in the energy sector?

Innovations are mainly expected to speed up the development and introduction of low-carbon clean technologies. In the energy sector, there is a particularly great need for breakthroughs in the storage and balance sheet management of variable renewable production (wind and solar power). It is therefore worrying that there is now less innovation in the field of clean technology.

Popp et al. (2020) analyse the possible reasons for the decline in the number of clean energy technology patents. Firstly, the energy sector has been traditionally characterised by a highly concentrated and capital-intensive production method based on rigid long-term structures. In Finland, a good example of this is the debate on peat. Moreover, the research and development work in the energy sector has been the domain of large companies, which have changed more slowly than similar companies in other fields. Secondly, innovations in new energy technology require more expertise in such high-tech areas as information technology (IT) than in the past. The IT field is more agile and modular, which means that small enterprises can also do well in that sector. For example, mutually compatible IT applications are required for the automation of energy use in buildings and for mobile devices.

What would be needed to boost innovation in clean technology?

Is the path taken by the EU also the path Finland should take?

According to the European Commission, the Paris Agreement on climate change could act as an important catalyst for manufacturing industries in the EU by the middle of this century. In the EU, carbon emissions pricing, such as emissions trading and environmental taxes, are used as incentives for reducing emissions. In the scenario produced by the Commission, one tonne of carbon emissions would cost EUR 250–350 by the year 2050. The strategic aim of the EU is to gain a substantial market share in climate change mitigation and adaptation technologies, and it believes that the market share of these technologies will grow at an annual rate of EUR 1–2 billion by the year 2030.

Finland has been eager to present itself as a nation of engineers that creates practical solutions to meet its own needs and the needs of others. We have perhaps left the sales and marketing of the solutions to others.

Despite our solution-centred rhetoric, there has not been any significant increase in Finnish investments in research, product development or innovation for many years. Like Finland, South Korea, Israel and Taiwan are also countries with few natural resources and small domestic markets and they also have to cope with rising labour costs. However, they have chosen a different path and can now boast impressive patent portfolios (Barnett 2020).

When examining the downward curves in Chart 1, pessimists see a lost opportunity. Optimists, on the other hand, would say that Finland has not yet lost any ground and that it is not too late to make the necessary corrections and to progress towards better times.

References

1) Barnett, J.M. (2020) ’Patent Tigers’ and Global Innovation. Regulation 14-18 (Winter 2019–2020).

2) COM(2018) 773 A Clean Planet for all – A European strategic long-term vision for a prosperous, modern, competitive and climate neutral economy.

3) European Commission (2018) In-depth analysis in support of the Commission Communication A Clean Planet for all.

4) Valtioneuvoston selvitys (2019) EU:n komission tiedonanto vihreän kehityksen ohjelmasta (Green deal) 11.12.2019.

5) Huhtala, A. (2019) Ympäristö, sääntely ja kasvu, In Honkapohja, S. & Vihriälä, V. (eds.) Suomen kasvu – Mikä määrää tahdin muuttuvassa maailmassa? Etla and Paulon Foundation, Helsinki pp. 177–192.

6) Popp, D., Pless, J., Haščič, I., and Johnstone, N. (2020) Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the Energy Sector, NBER Working Paper 27145.

Anni Huhtala

Blog

Blogit

Energy, climate and environment

Environment, energy and climate policy

Press release

cleantech

climate policy

economic growth and environment

energy policy

environment

environment economics

environment policy instruments

environmental and resource policies

environmental policy

international environmental agreements

new technologies

renewable energy