Activation model made evaluating the basic income experiment more complicated – or did it?

25.6.2020 Blog Kari Hämäläinen, Jouko Verho

The activation model made interpreting the employment impacts of the basic income experiment more difficult, but does it really matter? In any case, few employment schemes have been evaluated with such accuracy: the employment impacts of basic income have been so small that it can never be the first choice when the aim is to boost employment.

We recently published the final report on the basic income experiment, which contains an assessment of its employment impacts, as laid out in the preliminary plan. In the preliminary plan, the researchers define the manner in which the subject is evaluated. This helps to prevent any unconscious or (in the worst case) deliberate picking of suitable evaluation findings. Watertight arguments must be presented to support any deviations from the preliminary plan.

The evaluation showed that employment among the test group members increased by six days during the second year of the basic income experiment (between November 2017 and October 2018). The employment boost was statistically significant even though an increase of less than a week can be considered fairly modest against the background of the generous employment bonus offered as part of the experiment and the participants’ livelihood. No significant employment impacts were noticed during the first year of the experiment.

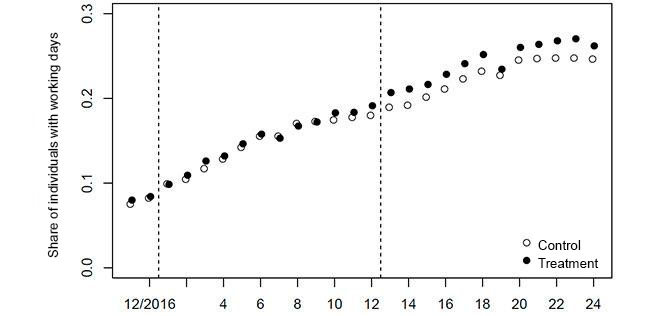

It was decided in the preliminary plan that this particular review period would be adopted so that the evaluation of the impacts of the basic income would not be affected by any adjustment periods at the start and at the end of the experiment. However, not even the most thorough analysts could have foreseen the Government decision to introduce an activation model for the unemployed as of 1 January 2018, which was in the middle of the review period. The chart below shows how a gap arises between the employment levels of the two groups of the basic income experiment as the activation model is introduced.

Figure: Monthly proportion of employed persons among the participants of the basic income experiment. The activation model entered into force during the 13th month of the experiment.

Employment impact 1.5–6 days

The activation model as such did not have any effect on the research design of the basic income experiment. Randomisation was used and as a result, comparing the employment trend among the test group with the control group produced a reliable estimate of the difference between the two groups. However, we still have to find out whether the estimated six-day difference was due to the basic income or the activation model or the combined effect of the two. Unfortunately, we will never know the answer to this. This is because the activation model was implemented in the traditional manner as a scheme applying to all unemployed jobseekers simultaneously, which means that its impact cannot be reliably determined.

In theory, the basic income experiment could be used to assess the impacts of the activation model if the basic income recipients had been left outside the activation model. However, this is impossible for several reasons. One third of the basic income recipients continued to apply for unemployment benefits during the 12th month of the experiment, and as a result they directly exposed themselves to the activation model. Furthermore, the activation awareness prompted by a huge media circus and the increasing activation of the control group also indirectly exposed the experiment test group to the activation model. Thus, separating the impact of the activation model from the impact of the basic income in this manner is also out of the question. Facing this challenge, we can put the employment impact of the basic income experiment at between one and a half days and six days. The lower limit is determined on the basis of the statistically insignificant point estimate for the first year of the experiment (when the activation model was not yet in effect). By setting the first year’s result as the lower limit, we make allowances for participants adjusting their activities during the first months of the experiment. At the same time, the result of the preliminary plan analysis framework sets the upper limit for the employment impacts of the basic income.

Basic income would not boost employment

Setting the upper limit of the employment impact at six days may be an erroneous interpretation if the activation model boosted employment among the control group more than among the test group. This could be theoretically possible because the activation model had a particularly strong impact on the control group. However, this view is not supported by the research findings. If anything, employment in the control group weakened when measured using the employment indicator defined in the preliminary plan. There are two reasons for this.

Firstly, the control group spent slightly more time than the test group in the activation arranged by the employment administration. As a result of the modest employment impacts of the activation measures, this also meant that the control group was not equally well-placed to work in the open labour market. Secondly, the control group was more frequently employed in occasional jobs than the test group and in these employment relationships, the daily wages were below the level set in the employment indicator. It may well be that working for the 18 hours required under the activation model during a period of 65 payment days was sufficient for many of the control group members.

Ultimately, this is primarily a communication challenge. The fact that the impact of the basic income experiment was limited to fewer than six days each year will probably not make basic income a high-priority employment policy measure. At the same time, however, few of the schemes proposed as employment-improvement measures have been assessed as thoroughly and credibly as the basic income. If the activation model had not been introduced, we would have an even more accurate point estimate of the impacts generated by the basic income. However, would an employment impact of, say, two days have changed the interpretation significantly? In fact, it may only have rendered it statistically insignificant.

Research report (in Finnish):

Kari Hämäläinen, Ohto Kanninen, Miska Simanainen, Jouko Verho: Evaluation of the basic income experiment - final report: Register analysis of its labour market impacts. VATT Muistiot 59. Helsinki 2020.

Jouko Verho

Kari Hämäläinen

Blog

Blogit

Column

Government Institute for Economic Research

Labour markets

Social security

activation model

basic income

employment

innovation policy

randomized field experiment

social benefits

social security

unemployment